(Gender, Culture and Sexuality)

By

Myra C. Beltran

First published:

“When Body becomes Writing,” Review of Women’s Studies: Discours(s), Sexuality and the Arts, vol. xvii, no. 1-2. 2008-2010.

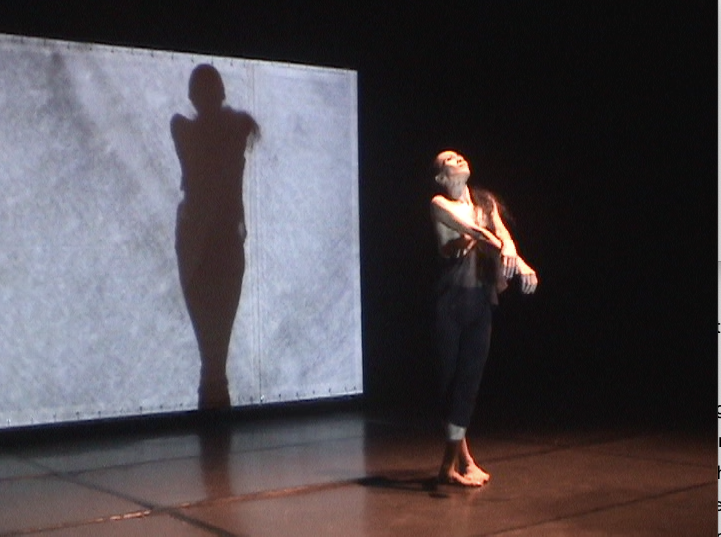

Myra Beltran in “Scarred is Beautiful”

at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Tanghalang Huseng Batute, 2004

Dance is firstly, an experience. Writing about dance could then be an ambiguous, perhaps self-defeating enterprise.

Prior to the 1960’s, those who wrote about dance had the goal of capturing its evanescent nature. A split had occurred between writing and dance. Where heretofore, dance writing had been about notating the steps of dance, when it came to be tacitly acknowledged that dance is an ephemeral art-form, “vanishing at every moment,” the writing on dance purposefully was made to “correct” this “basic deficiency” of dance. Writing on dance served to document the dance and in this way, was said to have gone beyond dance’s basic flaw, which is its “specific materiality,” to allow it (dance) to enter the world of ideas, embodied in writing.

To “cure” this generally perceived “art of self-erasure”[1], writing about dance was more or less, descriptive of what had occurred, relying on optical data, in an attempt to document the occurrence of dance. Writing was a “privilege” of those who had witnessed the live occurrence of dance. Describing the event meant that one was removed from the event. This is the split between dance and writing. In a sense, writers were working against the inevitable / main / undeniable characteristic of dance, which is its ephemerality.

In the 1960’s, Jacques Derrida’s critique of Western metaphysics allowed a re-thinking about the relationship of dance and writing. Derrida’s concept of the “trace,” where he writes, “The trace is the erasure of selfhood, of one’s own presence, and is constituted by the threat or anguish of its irremediable disappearance, of the disappearance of its disappearance,”[2]liberated the writing on dance from the narrow confines of visual data. The notion that the trace is always signifying another set of traces also means that dancer cannot be pinned down to words – as soon as the dancer’s movements are perceived, they are also, vanishing at the same time. “Movement necessarily entails self-erasure,” [3] – this is dance, it disappears as soon as we perceive it.

Dance by this notion, then occurs in a signifying field or continuum. We might then state that not all of dance actually materializes as visible, or we can also then question to what extent dance is visible and what that visual data can tell us.

Hence, I shall plunge headlong into this writing about dance and my specific experience of it, in a manner that does not fix the frame in one visual field, and maybe, one specific, identifiable genre of dance. Rather, I shall try to locate my practice by referencing the various forces that impinge on my body, my dancing body, that is the source, verifier, medium of all the dances that I create. I wish to recreate for you the tactile experience of my dancing body and hope that I displace any of your inherited notions of dance, gathered most likely, from your visual perceptions of it.

Historically, dance has served as a threat of some sort (evidenced for instance, in the censuring of the practice of various dances in indigenous cultures by colonizers, an experience replicated in not a few number of colonized countries. In the Philippines alone, there occurred a ballet ban in the 1950’s for instance). It has been astute feminist writing that has pointed out that it is masculinity that dance is considered a threat to, hence, there is this fairly widespread notion that dance is a threat to masculinity – such that dance and femininity are equated with one another. In this paper, I shall then attempt to take that leap to where dance, and femininity, the feminine[4] intersect, through the experience of my female body, and ask how such have a bearing on writing. It is this “writing” that bears the relevance of this experience.

A little background:

I was trained in classical ballet, and worked professionally in ballet companies abroad (Germany and Yugoslavia) before coming back to the Philippines to join the main ballet company in 1987. It was abroad that I became thoroughly conscious of the historicity of the art-form and the inevitable intersection with the society at large, and how that society came to define itself through culture.

At a certain juncture in my career, it became imminent that I ask deep and basic questions about myself and my practice. More and more, I had been increasingly alienated from the sort of “excellence” in art that I was pursuing. My feminine body and very female experiences could not find complete articulation in the form I was dancing in. I desired to define myself completely as a dance artist living and working in the Philippines (where opportunities and resources are admittedly, scarce) and all that this would entail on a physical, aesthetic, financial, personal and spiritual level. I wished to re-think the premise of being a dancer in the Philippines (supposedly, a temporary landing area toward more attractive opportunities abroad), re-think the structures that support the dance, question the patronage that support an exclusive group, inquire on the values that are implicit in such a system, and discern in my culture the beginnings of dance or what dance means or it’s function in the indigenous cultures, prior to the classical form that I had been perfecting.

My first venture into unknown territory, which was to lead me in the direction I sought, was through the discourses occurring in the visual arts as practiced in the Philippines. At that time, it was the visual artists who were taking the lead of re-discovering the roots of art in indigenous culture (in my experience, this was through the pioneering members of the Baguio Arts Guild, who became my friends, notably, Santiago Bose, Roberto Villanueva, and Bencab). These visual artist-led collectives were rooted in the community, in an attempt to address the elitist practice of the art, heretofore advanced by a very centralized government and co-related cultural institution.

As a dancer, tired from the tyranny of “constant performance,” I wanted to discover another approach to dance and making dances. At that time, it was not fully evident to me on a conscious level, that what I was searching for were unique pathways to my mature, much-performed and very female body.

The act of doing “structured improvisations” within the framework of installation art as created by kindred visual artists (Bose, Villanueva, et al.) who were themselves breaking down barriers in the visual arts that confine their work to commodities, was a dialectic, a question of space. The act of losing myself in a different configuration of space, different from the two-dimensional frame of the proscenium stage which although my dancing body had learned to project as three-dimensional, this being the task of the dancer (showing three-dimensionality within a clearly-defined two-dimensional frame, ultimately, seeking to breach the fourth wall that separates performer and audience), liberated my inherited notion of space.

More importantly, improvisation gave primacy to intuition. An intuitive relation to space was an “assumed” if one had the “talent” or the calling, to choreograph (which was then different from being a dancer – supposedly, one could not be both without sacrificing “excellence” of the other). In other words, as I was conditioned to believe as a dancer within the structure of a ballet company, one either had the “choreographic bent” or not, with the implication that choreography is also an act of “genius” or “privilege.” Choreography, I was told, was a “calling” and not the discourse that I would later discover it would be. Having lost myself in a “borrowed” notion of space, as defined by a “co-conspirator” which at that time had been the visual artists, I entered into a deep dialogue with the tradition I inherited as a dancer, that would one day open the way for me, to eventually also be called a choreographer, and this time both a dancer and a choreographer (a dancer-choreographer) whose imminent voice precisely lay in the combination of both tasks. At that time, the term choreographer had an imposing connotation attached to it and I dared not attach the label to myself. It was reserved for those with commanding presences, who inspired both terror and awe in dancers. This was different from my modest goal of merely enjoying myself in the dance, dancing the dances that conveyed my womanly experience (versus the “ethereal spirits” of the ballet repertoire or the modern strong archetypes of the modern dance repertoire which I had been then dancing), and wanting to recover dance’s “rebellious” spirit which I had so related to at this point in my life. Soon, I settled on using “dance artist” as the label to call myself, as if to shyly reconcile “dance” and “visual artist.” I shied away from using only the term “dancer” which seemed degrading, marginal. In hindsight, “dancer” when used in everyday language, connoted female, for sheer entertainment, almost derogatory (at that time, the Philippines was exporting quite a number of “dancers” to Japan as “japayukis,” implying dance as a front for perhaps, prostitution). I do not shun “entertainment,” and truly, dance performance has an “entertainment” aspect, and it is naïve or maybe arrogant to think otherwise. My contention is when it is used as if this is all what dance is about, to relegate it to a minor art, implying that it cannot enter the world of ideas embodied in the discourses of the “arts.”

At this time, I perhaps wanted to stand on equal ground with all other artists (admittedly, coincidentally and mostly, male) while stating that my medium was the attractive, elusive, betraying, ambiguous, human body – the one not given to codification, the one that is “slippery” as far as theory is concerned. In retrospect, perhaps it was the Muse of Dance herself – the Feminine, wanting to assume her place in the realm of arts, in all her ambiguity, in all her mystery and evanescence. I rebelled against “sheer entertainment” as if to connote commodity, commodity of the human body. This was the content of my primary “rebellion” – my insistence in “owning one’s body” – away from blatant or implied commodification.

By 1994, I produced my own full evening’s choreographic work. This first concert was called “Women Waiting,” in inspiration of a print with the same title by Benedicto Cabrera, or BenCab. This print[5] simply had a group of women of peasant origin in traditional dress at the turn of the century, seated and standing, witnesses to history, and “waiting.” By 1995, after having attended the NGO Women’s Conference in Huariou, China, with an overflow of female energy around me, the conscious direction I had taken became markedly articulate for me.

1995 was the year the name Dance Forum for my group, arose. After experiencing an almost empty house at the theatre for a repeat of this first concert, one writer describing me as “being on a lonely path where no other Filipino dancer has treaded,” I realized the complexity and totality of the journey I had undertaken and concomitantly, that I was marginal twice over, being both a woman and a dance artist. It was necessary to claim my space, and with this act, truly claim to be a “daughter of necessity.”

The exchange was a complete letting go. No longer confined to the proscenium stage and by extension, thrust outside the entire culture that ran parallel to this and “culture” as such (the bias that only in a hegemonic center is “culture” created, in a distinction of high and low culture), I ventured to transform the studio that I work in into a performance space, in a complete tangent from my entire training.

In effect, I had decided to cease being a “woman waiting” and was now actively shaping the history I belonged to. In essence, I sought belonging to a “forgotten” tribe of women artists, healers, bearers of the community’s stories, wishing to mark the passage of time in contemporary rituals through dance. This was in 1997.

Alone, left to my wits, I discovered that in order for me to sustain my work and answer my own questions, I had to be free from that outer, censoring and perhaps, “male” gaze which had been part and parcel of my entire dance training and hence, concept of myself. I had to be free of any outer images I had of myself, create new empowering ones of my own, and this was necessary, for me to even move. Dancing is a process of entering into a form, which form is determined by one’s image of one’s self. It is a process of self-determination and not a mere use of muscles. In order to overcome inertia that is the start of movement, one must have a complete image of one’s self, because now alone, no one else was there to impose or compel one to move. It became necessary for me to know and be in touch with what moves me, and then re-learn how to move again, to find the form from within myself. I was discovering that one’s sense of space, how one locates one’s self in space, is itself a power. This power is an ability and a commitment to be present at everymoment, what Clarissa Estes describes as a “power of one’s soul” and I was re-discovering this power.

It was through such discernment that I began to train myself and create dances. I was able to see my body as shifting through form and formlessness, understand and truly sense the alignment of my bones, the interaction of thought, breath, and movement, and I was able to release into the ground, not just all the tension I had accumulated through years of performing, but tension as the result of deep conceptions I had of myself as a woman conditioned to conform. The “letting go” is an on-going process that gets deeper through the years. In this way, I was able to heal my very tired body. Now, I was dancing as the woman that I was and my body transformed. It also transformed into the ground of my practice.

The non-attachment to concepts / ideas but the openness and willingness to experience things gave me the fluidity I value in dancing and it allowed me the freedom to dance without compulsion. This also allowed me to put forth an aesthetic that was anchored in the specificities of my body, and not as previously experienced, in prescribed classical or modern forms, and it was then that I knew I would no longer be judged according to the standards that had heretofore, oppressed me as a dancer. Space was not there to conquer, but space was there to have a relationship with, to be one’s partner. Eminent Indian dancer Chandralekha has said, “space is the encounter between moment and relationship,” meaning space is not a given, it is constructed through relationship at every moment, and hence, is constantly shifting – it can be one’s partner, in other words, and not one’s oppressor.

To put it briefly, I was reclaiming my body as home, the home through which I began to understand all my years of training, the confusing dance styles / techniques I had experienced, and it was the way I understood myself as a woman, what I wished to express and in what context – in short, the politics of dance experienced and articulated through my body.

In the subsequent years of the late 90’s, “techniques” now related to the practice of contemporary dance, have arisen to re-create this experience, such as release technique, body-mind centering, etc. My point is that although I did not “learn” these techniques where they are “codified” (mostly, in the West), I was humbly discovering it thru my everyday work, without authoritarial approval, through openness, willingness. I was being bred as a dance artist in my context in this country, evolving my own dance technologies, and I was now truly a dance artist living and working in my country, the Philippines.

The concept of that notion of space and the body extended into the configuration of my studio-space, the space I had chosen to create and perform my dances. It was as if while I was centrifugally dancing toward articulating a vision, a parallel centripetal movement gathered a community around me, to affirm my aesthetic choices. The studio space became a womb, a ritual clearing, a container that allowed dance to be seen at its barest and most vulnerable. The resonance I eventually encountered for such a space and its aesthetic became what would become an “independent dance movement” in the Philippines.

Independent dance does not mean one is free to do whatever one pleases. Rather, it means having the commitment to work everyday and listen to one’s body and create one’s language from there. It is “independent” because it is outside a certain “system.” It is independent because one’s experience can define one’s language. Feminist concerns privilege the “authority of experience” and this is how I venture to state that the move for independent dance has a feminist articulation (this apart from the fact that I am female, and supposedly, by dance historian Basilio Villaruz’s estimation, the most female of Philippine choreographers.[6]). Villaruz writes, “While other female (and male) choreographers present the typical images of the feminine and masculine, she explores the dark recesses of the intuitive and natural (even cosmic) worlds. While other female choreographers show formal structures like the male choreographers, she avoids such explicitly rational approach. She is instinctive. She takes on rituals, affective and effective on ritual grounds. Beltran has profound things to say; visual, musical and other artists have found affinity with her processes. Her oceanic, mythic imagination appeals to their unfettered minds.” Process, collaboration, valuing the parts as constituting the whole, re-thinking what is “small or inconsequential” as opposed to what is “big and important,” these were conscious feminist choices, and it informed the “birth” of independent dance in this country.

“Moving to centre”

The year 2004 saw the palpable presence of an independent dance community. Where heretofore, contemporary dance activity occurred in larger intervals of time and in isolated projects, by this time, independent dance groups declared their studio spaces as alternative performing spaces in a clear declaration of sustaining contemporary dance activity. (These activities saw Airdance, Dancing Wounded Contemporary Dance Commune, Chameleon Dance Theatre, an energized U.P. Dance Company, and a primarily visual arts space, Green Papaya Art Projects, engaging in contemporary dance activity). This is not to romanticize the whole movement, because the effort to create it and the biases met against what it symbolically meant was, to a certain extent and still is, very real and present.

The bias for established artists or “masters,” or international competitions were still the organizing principle by which public funding for the arts came to be allotted in the early years of existence of this alternative performing space. Pain-staking effort was required to acquire minimal funding. Using the economic framework of cost / benefit analysis for projects, initiatives such as those of independent contemporary dance, especially in its beginnings, pale in comparison because these frameworks do not capture the qualitative impact of these projects and their labor-saving mechanisms remain unquantified and invisible (mostly, independent dance artists both choreograph, perform, do fund-raising).

By 2002, this had changed somewhat with the acknowledgement of “young and innovative” as a theme for a national project, by the main body for public funding for the arts, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts for its February Arts Month. By 2004, when other independent dance artists (mentioned above) most of them having gone through “apprenticeship” or having premiered at the studio-space I had created, had opened their own studios as performing spaces, affirmation for such a community was inevitable.

In 2005, initiatives to create consolidated projects for this choreographers’ network were successfully undertaken, in the form of innovatively-structured festivals (namely the Contemporary Dance Map 2005), valuing the use of alternative performing spaces. The momentum of these efforts empowered individual members of the network to launch their individual careers in contemporary dance and also caught the attention of the main cultural institution, the Cultural Center of the Philippines, for the network to re-create these initiatives within their venues. This “national” project materialized in mid-2006 as the first independent contemporary dance festival, called “Wi fi Body,” to connote a network of players comprising the body of independent dance, autonomous but connected. “Independent dance” had turned into the buzzword of dance, identifiable as a “label,” perhaps, no longer as “marginal.”

I headed these initiatives. Their conceptual and organizing frameworks arose from my experience as a choreographer. By this time, choreographing bodies meant to me, not merely choreography for moving bodies onstage, but ways to organizing the flow of movement around the “performing movement.” In a sense, it was a “choreographic mind” that moved these initiatives forward. These initiatives were also meant to create infrastructure intended to create sustainability for this movement of bodies into history, because this is what these initiatives implied – creating history, dance history and beyond.[7]

Negotiating relationships

In the global world, where technology has allowed “independence” in the arts to exist, and for individual careers to flourish, the “networking” that happens on the “international stage,” so to speak, also has engendered a parallel movement to connect with those who work locally, to resonate “with one’s own.” Our choreographers’ network is no different from such initiatives.

Initially an “informal” network of actors, bound together by our desire for more visibility for our art-form and also primarily to resonate with each other on an artistic level, this network becomes “formal” precisely, due to the efforts to acquire more “visibility,” necessitating “consolidated” projects. Individual differences and individual strategies for putting forth a work borne of specific material conditions is the kind of diversity that is the idea behind the formation of an artist’s network (it not being a dance company with one sole artistic vision and organization) and this is also its strength. How to respect these differences, while still moving forward as a group to advance the group’s “advocacy” requires a constant process of negotiation amongst all players. This is dramatically heightened when a government cultural institution “intervenes” via a cooperative project – the network is forced to define itself on the most basic level.

In a sense, a project in cooperation with a main government cultural institution implies that activity from the “periphery” comes into the centre. Artists embark on this journey with the vision that their efforts could influence cultural action, if not cultural policy itself. Not everyone is able to discern this “shift” from an informal to a formal network and what all of this implies. It is even more problematic when the “aesthetic issues and concerns” of practicing choreographers become entwined in the politics of moving into that “centre” itself. For some, their aesthetics are irrevocably connected to the physical configurations of their space and cannot or should not be transplanted, or that administrative concerns of that “centre” actually run in contradiction to their very philosophies as artists. These differences in strategies with regards to our position vis-à-vis the government cultural institution came to foreground in our recent experience collaborating with a government cultural institution.

One of the premises of the “move to independence” that my practice initiated is to respect and uphold the uniqueness of each choreographic voice and to not judge by pre-determined or inherited standards. The tenacity of “implementing” this premise means that various discourses are allowed to be discussed freely, within the work and outside it.

Thus, I wish to digress a little and explain the emergence of such strategies and their relations to developments in theory and how these have played out in the practice of contemporary dance. By doing so, I wish to locate some of the practices that have come about as a result of my “move to independence” and how this has “moved” through time in contemporary dance practice in the Philippines:

Current contemporary dance practice, its main proponents being based in Europe, evolved from the modernist “ruptures” which started at the beginning of the 20th century, which liberated dance from its conventions and codifications, this last being most articulated in ballet. Isadora Duncan (turn of the century) in her flowing tunic, inspiring a return to Greek iconography was the first to go barefoot and declare emancipation. Martha Graham (during the 1920’s) is responsible for what we call “modern dance” which stylized the action of breath in a form (contraction and release) and codified “modern dance” as a technique. Onward, Merce Cunningham (in the 60’s) brought dance outside the confines of the proscenium stage, doing site-specific work that espoused randomness in the composition of dances. The Judson Church movement (late 60’s and 70’s) proclaimed a manifesto of dance that rebelled against their “modern forebears” (in a case of a “reversal” of the project, its popular exponent, Martha Graham, bearing the brunt of the “accusation”) and declared “no to spectacle, no to virtuosity.” This supposedly marks the start of the postmodern dance movement.

The 1990’s saw dance makers re thinking dance’s formal and ontological parameters which is their 20th century legacy.[8] The practice of dance, proposed by a number of practitioners, shifted from a theatrical paradigm (from its tanztheaterpractice, its primary exponent being Pina Bausch of Wuppertal Dance Theatre, who continues to be influential) to a performance paradigm. This it has evolved by assimilation of the theories of minimalism, conceptual art and performance art.

To put it briefly, the important element which defines these works, the articulations being many and varied, is that its dance makers are unconcerned with defining their work within the ontological, formal or ideological parameters of something called, or recognized as “dance.”

Thus, they have placed the dance in a kind of ontological and political “trap” – as if dance did not know the ground on which it stood, and what it can stand for.

There are many names by which these practices are called (new dance, performance art, live art, happenings, events, body art, body installation, physical theatre, etc.). This is exactly its premise – that it refuses to be boxed in categories and wishes to retain its unstable nature. The far end of this is to forever undermine the possibility of representation, and to question movement as the essence of dance.

In current contemporary dance practice in the Philippines, which articulation came to foreground at our recent festival (and it should not be overlooked that these initiatives derived from autonomous work in alternative performing spaces) the question, in relation to “international” developments and trends in contemporary dance, is: what happens when such experiments are recreated in the Philippines by contemporary dance practitioners? What aspect of the experiment is transplanted? Do we participate in such experiments or does our refusal not to participate, indicate our insularity, refusal to engage in theoretical artistic concerns which seem to be international in influence? If we refuse to participate in such experiments, are we rejecting an entire philosophy, isolating ourselves even more, or merely rejecting these strategies, which are space and time-bound?

Perhaps it is occasion to discuss such strategies, not with the intention of curtailing these experiments but merely to clarify (from one person’s point of view) or position these strategies within the greater whole of the practice. Because this is really the premise: the subject-position – and the implication that the practitioners must be conscious of their own subject-position.

This gives us pause to reflect that a contemporary dance strategy evolved out of a Western context takes with it much of what that Western culture has evolved itself – more pointedly, that contemporary dance practice from the West benefits from the infrastructure of theatre, the arts, public funds and support, a developed arts market that exist in such a society. Contemporary dance practitioners’ from the West contention of the “instability” of the ground in which dance stands is contained within that “infrastructure” and when examined further, their contention of the “impossibility” of representation in dance is contained still, within the field of representation which is their legacy from the entire Western discourse. A mere “transplant” by local contemporary dance practitioners, without a critical approach, becomes a contentious enterprise for both audience and especially, the artist, who then must retreat into the “incomprehensibility” of the audience and perhaps, own colleagues, of a work put forth, and like any “misunderstood” artist rave against the entire infrastructure – if it does exist. And herein, lies the local reality, that as local dance artists put forth their work, they are at the same time, building its own infrastructure. For local dance artists, this infrastructure does not exist, it has to be built from bottom every step of the way. Every person who could be interested in dance must be coaxed into it, every young dancer who wishes to push her / his physicality must be nurtured and opportunities and venues sought for, every choreographic decision contains the responsibility for the understanding and acceptance of the art-form by recalcitrant audiences, this is the local contemporary dance artists’ burden: to build and thus, affirm, while at the same time, creating critical attitudes for both audience and especially, for those who are the medium of the dance – the dancers themselves, in their specificities, in their material conditions. The undeniable requirement would then be that local dance artists, in their practice, must be thoroughly aware of their own subject-positions, which I dare say, must necessarily be that of a post-colonial subject if she/he intends to live, practice and be present in the Philippines. It is my belief that local dance artists cannot deny this position, even as they move to emulate movements in art developed abroad, keep with global “trends” and strive to be “counted” in the global arena of art production. A dance practice that is grounded locally (as distinguished from a practice that is geared for an international market) inevitably encounters post-coloniality. It is just a question of how strategically the artist reconciles with such context.

The politics of dance

Earlier in this essay, I mentioned that Derrida’s critique of metaphysics and by implication, the post-modern movement, in its importance of liberating dance and dance as text from the confines of mere “visual data.” In the Philippines, directly or indirectly, such a critique enabled to a certain extent, the “move for independence” in contemporary dance, as articulated in this article. Indeed, many “gains” have been its result. Contemporary dance in the Philippines has put forth issues about concepts of the body (questioning the inherited notions of beauty and perfection), has advanced the use of alternative performing spaces and liberated dance from the confines of the proscenium stage and its accompanying market-driven programming (allowing more creative voices to emerge), has resulted in a plurality of aesthetics as material conditions in the creation of dance are now accounted for in the aesthetics of a work (liberating it from the need to have “high” and expensive “production value” in order to be “valid” as a work). But perhaps, it would be worth clarifying at this point that what this critique of metaphysics implied is a certain “play” – an opening up of possibilities of representation by way of stating its impossibility, but not to bring it to its “logical” end (because precisely, it critiqued that “logic”) by concluding a literal “anti-dance” position, itself a strategy and not a nihilistic result of that premise. “Appropriations” of theory to practice, it (choreography) being a critical practice, must itself also be critical.

Perhaps, it is time to pause and reflect on the gains of independent contemporary dance in the Philippines, not to invalidate it, nor retreat to a notion of dance whose primary aim is to present it as a “fetishized” and final product, but merely to understand its current footing. Living and working in the Philippines, one is necessarily and inevitably a post colonial subject. One cannot escape such burden, responsibility, and ambiguity as an artist. Contemporary dance practitioners in the Philippines must be aware of the use of choreographic strategies which derive their philosophy from a post modernist premise and discern its implications and limits to a “post-colonial.” As has been said, the post modern crisis of meaning is a crisis not everyone shares[9] and we must be sensitive to the finer aspects of the argument and its implications to our specific realities. It is our responsibility as artists to not constantly undermine our identity lest it weakens our ability to resist. Instead, we must embrace all our actions as a complete living through of a very real and present struggle.

As contemporary dance artists in the Philippines, how does one swim in this tide of market forces, including that of the marketplace of ideas?

I believe, after all the years of work and struggle, that the answer is to still keep renewing and constantly “reclaiming the body as home.”[10]

It is in the everyday work that the answer lies. Thought is a motion[11] and mind and body are conjoined in one instant in the rendering of movement, of form in dance. To understand and participate in the physics of dance – the breath, the flow, the weight, the momentum – one must thoroughly engage. The post-modern “ironic distance” is relevant when we re-think our conceptual frames as choreographers, but not in our daily work at the dance studio. The constant fleshing out, the humble appreciation of one’s abilities and acceptance of it, the inevitable existential decision made at each moment to move, submitting one’s self to the art, the unwavering faith for the power and relevance of the art-form, the letting go and surrender to the stream of life that is the essence of dance, this is the “antidote” for confusion in a global, post modern, fastly-changing and irreverent age, full of ideas. It is through pain-staking physical, intellectual and emotional effort that one is able to find one’s grounding and achieve stability in “unstable” ground – a stability that enables one to go forward and continue the struggle for self-determination which is still the task of any post-colonial artist in the 21st century.

Through this everyday work, dance becomes grounded in the historical and material body of the dancer. The dancer has “agency” in the determination of the meaning of a work, her / his politics are embedded in the work. A dancer threshes out these choices alone, and everyday, where insights into what the work could be or could mean emerge in those liminal spaces of the psyche when one approaches a movement or brings it to repose. These decisions come into play in the manner we, as audiences, “interpret” the meaning of a work in dance. This ever-present body speaks to us, as audiences, in a very concrete way about the world inside and outside, boundaries being rendered porous.

By thus, submitting the determination of a dance to the material conditions of its embodiment, we de-stabilize the play of the “trace” of the Derridean model. This is the limits of deconstruction for dance and performance studies because it does not take into account the dancer in all her / his gendered, cultural and political distinctiveness[12] – in short, the subjectivity of the performer. A dancer’s totality, her / his politics, is included in every decision to move, and this body is ever-present and creating its own history. This is markedly so, for one who both choreographs and performs her / his work

Dancer-choreographers make choices that are political:[13] in the way they see dancing bodies, in the way they determine what beauty means, in the images they present, in the manner by which they expose themselves wholly to the audience. They are both present as dancers while their movements are disappearing in time, and the choreographic decisions which comprise their dance are themselves, re-presentations. This is what Phelan[14] refers to when she writes about “disappearance” in dance and proposes that the art’s (dance’s) “representational frame” works from within a tension to which presence, disappearance, and re-presentation all contribute. Movement necessarily entails self-erasure, we perceive it as it is at the same time vanishing. But this self-erasure is contained within “fields of representation, of disciplining, of embodiment”[15] and is grounded in the historical and material body of the dancer – the dancer is ever-present, or in terms of the Derridean model, presence returns while also creating a history that is always “on the verge of own withdrawal.”[16]

At the start of this essay, I ventured to introduce notions of the relationship between body and writing. By tracking the development and growth of one effort to “reclaim the body as home,” I have in a sense, grounded the movement of independent dance in the Philippines through the experience of one particular body, and this, a woman’s body. However, this is not merely a personal journal of that practice because this practice dared re-think notions of space that has extended to the use of alternative spaces for dance. This is now the locus of independent dance practice in the Philippines. Might this not be a form of feminist practice in dance? It is a practice grounded in the specificities of a particular body and not an imposition to others of an “ideal” notion of a dancing body. More pointedly, such practice by extension, acknowledged the uniqueness of each dancing body, hence, a diversity of bodies are now practicing as contemporary dance artists in the Philippines. Also, the “liberated” notion of space has engendered the use of alternative venues for performance, away from a centralized, controlling authority which exist through established mechanisms and in which spaces to question such mechanism did not previously exist. Would not this radical “personal” re-thinking, with its multiplier, rippling effects, be called a process that is “femininist”? Indeed, would there be fixed definitions of a “feminist dance” or is dance precisely, the always-constructed definition which this practice, as described above has advocated?

The more important point is that this practice has enabled a diverse set of bodies practicing as dance artists in the Philippines. As they say, the rest is, history. The self-erasure of dancing bodies, all belonging to a common historical and political realm, in their subjectivities have in fact, written (dance) history.

Here we come to a new relationship between dance and writing. In this essay, I have written of the history that my body has danced. The personal choices have been political, and because these have written history – history has inscribed itself on and in the body. Dance and writing have once again, become one. Body has become writing.

Myra Beltran in “Not Mine” 2005

commissioned by the Arts Development Association of Taiwan (ADAT)

[1] Influential dance innovator Jean Georges Noverre (1760) in his “Letters on Dancing and Ballets,” perceives dance as an art of self-erasure and “deplores” its evanescence, as he writes, “What are the names of maitres de ballet unknown to us? It is because works of this kind endure only for a moment and are forgotten as soon as the impressions they had produced.” This leads Noverre to the idea that the act of writing about is a “mnemonic supplement” for dance’s predicament, which is that it loses itself as soon as it emerges, and that to write about dancing is to fix it in the writer’s memory for future readers. (Body.con.text, Ballet international / tanz aktuell yearbook 1999, p. 84)

[2] Jacques Derrida as quoted by Andre Lepecki in Maniacally Charged Presence in “Body.con.text, Ballet international / tanz aktuell yearbook 1999, p.86

[3] Lepecki, p. 86

[4] Elaine Showalter’s definition of feminine, feminist, female in Toward a Feminist Poetics, The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory. Ed. Elaine Showalter. London: Virago, 1986. 125– 143.

[5] This print is by now Philippine National Artist, Benedicto Cabrera (Bencab).

[6] Basilio Villaruz in Three Men and a She-shaman. Manila Chronicle, June 1995

[7] Basilio Villaruz writes in Changing Faces and Forces in Philippine dance, Philippine Star, March 6, 2000, that “the rise of independent dance is a logical growth from Philippine dance history, specifically, that the 50’s saw folk dance achieve worldwide recognition, the 60’s started professionalization, the 70’s ensconced activity at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, and today, because the artists have grown, matured, or are, so to speak, “let loose” to unearth new viewpoints” in this era of globalization, the result is the rise of the independent dance community in small pockets all over Metro Manila, if not already in the provinces, such as in Koronadal, South Cotabato

[8] Further reference can be found in Andre Lepecki’s Concept and Presence: the contemporary European dance scene, in “Rethinking Dance History”, ed. by Alexandra Carter, Routledge, London, 2004

[9] I transcribe the statement of Linda Hutcheon from Circling the downspout of empire post-colonialism and postmodernism, in “Ariel” 20(4), 1989.

[10] This is the published article of Myra Beltran, “Reclaiming the body as home,” in Filipiniana On-line Reader for the Open University, University of the Philippines and as read in the World Dance Alliance Asia-Pacific Conference 1998, Manila and at “Dance and Gender Conference” by the National Commission for Culture and Arts, December 1998.

[11] Taze Yancik in Thinking/dancing: First Steps, in “Body/Language”, issue no.1, University of North Carolina, 1999, p. 14

[12] Franko as quote in Lepecki, Maniacally charged presence, p. 87

[13] Yanick, p. 14 says, “Choreographers and dancers are urgently involved in the consideration of the composition of bodies in space and time, their movements, gestures and limitations. So, if thought is the motion by which historically contingent configurations of power relations or states of power are interrogated and responded to, then the movement of dance could be seen as thought arising, out of an overall strategic situation to perform rearticulations of that situation, economies of space-time other than those of institutionalized habit, and to articulate that situation otherwise – a thought or resistance. This might be to say, moreover, that choreography and movement (some of it, at least) takes place in the gap between politics of the body and the body as the political; between histories of the construction of the body and the body as historicity, as materialization.”

[14] Peggy Phelan quoted in Lepecki, Maniacally charged presence, p. 87

[15] Lepecki, p.87

[16] Lepecki, p.87

Bibliography:

Beltran, Myra. Re-claiming the Body as Home in the Filipiniana Reader: A Companion Anthology of Filipiniana Online, ed. By Priscelina Patajo-Legasto, OASIS, University of the Philippines Open University, Quezon City, 1998.

Foster, Susan Leigh. Reading Dancing: bodies and subjects in contemporary American dance, University of California Press, 1986.

Hutcheon, Linda. Circling the downspout of Empire: post-colonialism and postmodernism, in “Ariel” 20(4), 1989.

Lepecki, Andre. Maniacally Charged Presence in “Body.con.text, Ballet international / tanz aktuell yearbook 1999.

———-, Concept and Presence: the contemporary European dance scene in “Rethinking Dance History”, ed. by Alexandra Carter, Routledge Press, London, 2004.

Nielsen, Finn Sivert, Cultural Networks and Mediating Elites, Paper presented at the Fourth Nordic Conference on the Anthropology of Post-Socialism, Institute of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark April 2002

Showalter, Elaine. Toward a Feminist Poetics, The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory. Ed. Elaine Showalter. London: Virago, 1986. 125– 143.

Villaruz, Basilio Esteban. Three Men and a She-shaman. Manila Chronicle, June 1995.

———-, Changing Faces and Forces in Philippine dance, Philippine Star, March 6, 2000.

Yanick, Taze. Thinking/dancing: First Steps, in “Body/Language”, issue no.1, University of North Carolina, 1999.