by Sylvia L. Mayuga

As published in Philippine Graphic Magazine, Vol. 21, no. 12, Aug. 23, 2010

The sixties rushed to the seventies with

Molotov cocktails shattering glass to a million fragments as the literary

grapevine buzzed: Barang, our poet’s poet Virginia Moreno, was writing a play

on La Loba Negra. Word was that Quijano de Manila and the Ravens were

encircling her, but before we knew it, she was suddenly in Paris with her writing. La Moreno was up to something to sit up for.

“Barang, ” her fond inner circle nickname, means magic in our native tongue. At

the eve of what she’d call “ley martillo,” Law of the Hammer a.k.a. martial

law, her “Onyx Wolf” won a prize in a Cultural Center of the Philippines

Historical Playwrighting Contest. Its

first performance directed by Rolando Tinio was no less than the inaugural

performance of the CCP’s Little Theater.

Lo and behold – onstage was a long departed

Aztec-Mejicana all in black: Itim Asú, Onyx Wolf in poet-speak. Her name was Ma. Luisa Bustamante, a wife who

became avenging angel of great courage and cunning after the brutal slaying of

her husband the governor general and their son. She went underground with her

daughter, living with peasants in the second century of enslavement by Spaniard

frailes and officials.

La Moreno’s fine hand continued turning the pages of two iconic 19th century

books. A legend more whispered about than visible in the archives or even

paintings by indios came alive before our eyes. Itim Asú’s long silence had ended in the first

of several incarnations among her adopted Indios in the latter 20th century

into the present.

La Loba Negra was born one dark

October evening in 1719 when Dominicans, Agustinians and Friars Minor

Franciscans – instigated by Jesuits, says the Wikipedia – entered the Palacio

del Gobernador in Intramuros, hacked the head of Governor General Fernando

Manuel de Bustillo Bustamante and finished the dark deed with a gunshot before dragging

his corpse down the palace stairwell.

In the brief two months of his incumbency, Bustamante had made powerful enemies in Manila, back when it was months at sea from Madre España, with the opening of the Suez Canal a century into the future. King Philip V’s order to Bustamante came with inherent danger: Clean up corruption in the galleon trade frustrating the Crown’s efforts to stanch Filipinas’ drain on the Treasury.

Bustamante’s friar assassins next freed

Francisco de la Cuesta, no less than the Archbishop of Manila, imprisoned for

corruption in Fort Santiago. De la

Cuesta hastily appointed himself acting Governor General, looming over

“cowering civil officials” as “investigation” exonerated all suspects. In faint justice, this Archbishop Governor General

was transferred to a Mexican diocese two years later. Itim Asú had lost her life by then, but

things were far from over.

After “the perpetual silence of the archives of the Royal Audiencia of Manila,”

as described by the writer Ninotchka Rosca, Virginia Moreno summoned Itim Asú back

to her adopted indios, still a live coal in the mourning black that became her

permanent cloak as she murdered priests in confessionals all over Manila and

Laguna.

Death had only imprinted her legend more deeply in racial memory, rippling to

the late 19th century in the book La Loba

Negra by Fr. Jose Burgos of GOMBURZA fame. It wove popular myth with skimpy

historical facts on this mysterious Aztec-Mexican woman’s fierce defiance of

white Spanish rule.

Bustamante could be assassinated. La Loba Negra could be gunned down. Their tale in a book could stoke the fires of

Indio resistance. But GOMBURZA had

committed the ultimate offense: calling the frailocracy “a complete farce,” and

daring to suggest it had enough Indio priests to break the monopoly of the

Spanish religious orders by secularizing the clergy. For that GOMBURZA was hung in 1871.

The hold of the Bustamante legend on Indio imagination had also compelled the

master painter Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo to exorcize collective shock in an

oil painting of masked figures rolling down the Palacio stairwell. It’s on view at the Museum of the Filipino

People but only after it was hidden for all of the 20th century. Isn’t that a

clear footnote in a still radioactive story, with more secrets hidden in the

archives of the only Catholic country in Asia?

In the continuing medieval drama of the clergy’s patriarchal sway over

Filipinos continuing to this day, condoms are denounced from pulpits as pure

evil, obstructing healthy sexual education for children. This clergy also excoriates a secretary of

welfare for making condoms available to the poor. Meanwhile, we behold tens of thousands of urban

poor children still increasing in numbers, begging for food in the streets of Metro

Manila.

Three decades ago, La Moreno heard the wolverine’s howl in dictatorship

aborning. Grafting elements from Rizal’s El

Filibusterismo to the text of Fr. Burgos’ book, she summoned back Itim Asu

in subliminal resistance. Adding details

of rich oral tradition in her native Tondo, once a seat of native royalty, Barang

chose Jose Corazon de Jesus, the lyricist of Bayan Ko, a.k.a. the balagtasan superstar Huseng Batute, as

both narrator and central character of “The Onyx Wolf.”

The balagtasan’s melodic improvised quatrains synonymous to

Tagalog theater tradition, and

Huseng Batute married to the zarzuela star Atang de la Rama a.k.a. La Tondeña

made perfect sense. In Moreno’s play, their

son was “Sandugo” – “one blood” – an echo of the ritual blood compact sealing a

bond of brotherhood unto death in our pre-Conquest islands.

Moreno had Huseng Batute direct and act in his own play in “The Onyx Wolf.” Sandugo confronts an American official in a poignant era of one Western colonizer replacing the old after aborting our revolution. This rich archetypal drama had only just begun to fascinate Filipino scholars and artists.

Ma. Luisa Bustamante’s legend glowed like a gem, deserving more than the third prize awarded to Moreno’s play. In 1972, enfant terrible Anton Juan directed it in an international theater festival in Liliw, Laguna, with Lolita Rodriguez leading an all-star cast. The CCP performance had modern dancer Alice Reyes playing the black wolverine as ley martillo about to descend on our heads. Decades later, it inspired Francisco Feliciano to an opera. By 2009, amid rumors of “martial law lite” should a female president “worse than Marcos” not get her way in 2010, Itim Asú’ became a talisman. The spell continues.

Lift Up

Your Race

“Take everything from me, my name, my honor

…Yes, take my daughter, the one I love most in this treacherous world, but kill

those executioners of your race. Lift up your race before the world. Make yourselves known as a people;

avenge the insults they heap upon you day by day…” – La Loba Negra

La Loba Negra had not faded from

Filipino imagination as the Third Millennium began. Former senator Leticia

Shahani loved the Alice Reyes performance enough to suggest a remake for International

Women’s Day 2004 to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts. But her fellow UP Humanities pioneer Virgie

Moreno was leery of “giving Onyx Wolf away” to just anyone. She knew it was a

crown jewel.

Myra Beltran had to win her trust. It began when the poet- playwright saw the

prima ballerina dance Mother Earth’s pain with Enrico Labayen in “Unearthing.” Mutual discovery continued in 2006 when Myra

enrolled in a UP masteral degree in literature, La Moreno’s UP home ground. Soon Myra was dancing the Moreno “Order for

Masks” – a truly memorable performance.

But it would take all of six years to gestate

what became the multi-media concert “Itim

Asú 1719-2009”. In this masterwork

of dance theatre, Myra, 49, emerged as consummate dancer and choreographer at

the cutting-edge. Her version of this

haunting archetype of woman’s wild inner nature wears the fullness of time like

a seal on its forehead.

On Nov. 27, 2009, the second evening of its inaugural three-day run, sounds

from Ninoy Aquino’s posthumous birthday celebration on Times Street drifted

like an unbidden older layer of history to Itim

Asú onstage in the Dance Forum

Studio on neighboring West Avenue. Word

of Myra’s artistic triumph reached Alfonso Yuchengco, Jr. a.k.a. Boyu on tribal

tom-toms. Funny – he was thinking precisely of dance for the family’s RCBC

theater stage.

He approached Myra at an art opening in January and Itim Asú was onstage at the RCBC Museum by Feb.24, 2010, this time coinciding with EDSA’s 24th anniversary. Curtains opened on a net of enchantment of a people’s living memory. As it grew on you, you understood why fellos artists sounded the first triumphant tribal whoops over Myra’s new theatre piece.

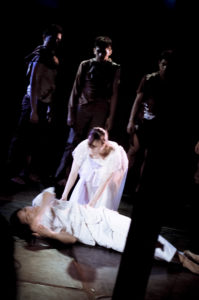

Blacks, whites, grays and touches of Carmelite brown moved to a seamless selection of haunting music. A giant screen with black and white images of historical scenes interspersed with a stream of ink blotches with touches of sepia back- dropped the dance. Slowly it came home: The screen was a projection of subjective reality.

In this realm of the unpredictable, no sooner were images and motions recognizable than they changed and flowed again like life, like art. The past echoed; the future glimmered in eternal now.

From her husband’s murder to his interment, Ma. Luisa Bustamante wore white, but in her solitary transformation to Itim Asú , she shed white for brown, and more darkening brown until she rose from agony, standing erect in avenging angel black, summoning the power of heaven itself to help her avenge her husband with her adopted Indios.

In an interesting insight on her creative process, Myra says the choreography came almost simultaneously with the streaming images on a rear projection screen in a livewire exchange of artistic ideas with the young filmmaker Sherad Sanchez. It didn’t start that way, but Sherad turned out to be her main visual collaborator in the serendipity of this project since birth.

Young dancers of the UP Dance Company kept the audience mesmerized with cartwheels and pinwheels, legs parting in very straight rows – upside down, sliding, coiling around their partners’ waists in wheeling pas de deux creeping like snakes, flowing like water.

In the wedding scene from El Filibusterismo, where Simoun intended to explode a bomb in a gathering of town worthies, guests wore coy stylized pañuelos over bare legs in impish deconstruction of the traditional saya. They sat with stretched legs on the floor throughout the number – writhing, kicking and laughing behind fans – flowers of Indio youth at the eve of bloodletting for nation.

Two Indios Bravos in Europe lay on their sides on the floor, heads propped by their hands, elbows on the floor, discussing news of approaching climax back home face to face. Sound track: Passages in the Fili read like the day’s news.

As dance, as theater, as film, Myra Beltran’s Itim Asú is an original – its aim at deconstructing history more than accomplished. To what end? The essence of the power of this performance is in inner reality, calling forth a deeper sensitivity towards self-awareness in a Filipino audience still trapped in a cocoon of a history so little remembered, so little understood. In Myra’s turn to channel Itim Asu, she opened no less than a portal to the womb of racial memory beyond words, breaching amnesia with art.

“It’s important to look back at these ‘landmark’ works of art to ground artists of the 21st century. My interest is how this drama shows the level of complexity with which we create meaning in history and how we as Filipinos readily blur fiction and reality, myth and history,” she says.

A thinking dancer and creative choreographer – grounded in the arts, now extending to film and the digital arts of wide coinage among the young – has produced a master work. Myra’s credo: “Dance is an art, a science, a way of life. I knew one had to go deep if one wanted to do it.”

That’s how she earned the right to dance history’s black wolverine in another dark political night for the Philippines. You know what they say: Night is darkest just before dawn. May Itim Asú find her way to all points of our archipelago and the rest of our global nation – live or on film.